Envy. Gluttony. Greed. Lust. Pride. Sloth. Wrath.

Atlanta classical radio producer and writer Noel Morris explains the history and context of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s The Seven Deadly Sins, which opens Sept 28 at Le Maison Rouge at Paris on Ponce.

By Noel Morris

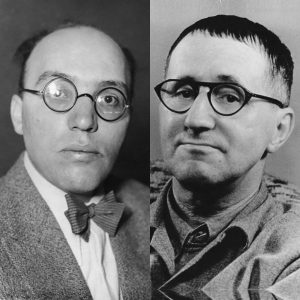

Kurt Weill was a refugee when he wrote the score to The Seven Deadly Sins. On March 22, 1933, he had dropped everything and crossed into France with his mistress and a small suitcase.

A month earlier, on Feb. 18, crowds streamed into theaters in the German cities of Leipzig, Magdeburg, and Erfurt to see Der Silbersee, a new show by Weill and playwright Georg Kaiser. Inside and outside the theaters, the SA (paramilitaries) staged raucous protests; they served at the pleasure of the newly appointed chancellor, Adolph Hitler.

“The audience that night knew it was a historic occasion, the end of something,” says Weill biographer Foster Hirsch. Weill was the son of a prominent cantor at the synagogue in Dessau. His star rose during the short-lived Weimar Republic, a creative pressure cooker of opera, theater, nightclubs, jazz, literature, visual art, and a heavy dose of political satire. (American audiences saw a bit of this world in the Broadway musical Cabaret.)

In the Weimar’s twilight years, Weill partnered with leftist author Bertolt Brecht to conjure a popular entertainment that synthesized the sophistication of classical music, the soul of jazz, and the wallop of a Marxist rally. Emblematic of their sound was the husky voice of Weill’s wife and muse, Lotte Lenya.

When Weill left for France in March 1933, he was estranged from both Brecht and Lenya (he and Lenya divorced later that year). Weill received a warm welcome, arriving on the heels of acclaimed performances in the French capital.

British arts patron Edward James immediately put him to work on The Seven Deadly Sins, a new ballet for the great Russian choreographer Georges Balanchine. Only two months passed between their first meeting and the first performance of The Seven Deadly Sins — although those months were not without drama.

Part of Weill’s genius lay in his ability to work within the cracks, whether bridging musical styles or art forms. Not shy about his standing in the cultural universe, the refugee composer negotiated to add to the effort a literary partner, one of “equal stature.” Billing The Seven Deadly Sins as a “ballet chanté” (a “sung ballet”), Weill offered the project to Jean Cocteau, who declined. James then pressured him to mend fences with Brecht.

Weill called Brecht “one of the most repulsive, unpleasant characters on the face of the earth.” Brecht, also a refugee, scoffed at James’ “bourgeois” project but couldn’t bring himself to say no. He needed the money. So he joined Weill in Paris, giving the work 10 days of his life, and then returned to Switzerland. This was Brecht and Weill’s last collaboration. Lenya sang the premiere.

The Seven Deadly Sins is a smart, ironic, and compact satire about a small-town girl who travels from city to city for a noble cause: to earn enough money as a dancer to build a home for her family. But this isn’t an allegory about small-town values and big-city vice. This is a drama that rages within the human heart, whatever the circumstance.

By splitting the principal character into two performers — Anna I and Anna II — Weill and Brecht give us a window into the young dancer’s inner dialogue. With each stop on her journey, she struggles with one of the seven sins, but Brecht’s book is far from unambiguous. The characters tend to commit one deadly sin to avoid another.

In the movement labeled “Anger,” Anna I scolds Anna II: “If you take offence at injustice, Mister Big will show he’s offended. If a curse or a blow can enrage you so, your usefulness here is ended.” In other words, Anna I justifies committing the sin of sloth (inaction) to avoid the sin of anger, although one senses that greed is her true mistress.

“Think of our house in Louisiana! Look! It’s growing! More and more it needs you!

Therefore curb your craving. … Gluttons never go to heaven.”

ANNA’S FAMILY

The Seven Deadly Sins

The story takes place in America. Over seven years, Anna travels from city to city as her family cackles about virtue, always with an eye on the money. The family’s presence is particularly oily, with music that pivots between church chorale and barbershop quartet. Notably, the mother’s voice is sung by the bass.

W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman prepared the English translation of The Seven Deadly Sins. The original score features a soprano as Anna I, but the publisher offers an arrangement for a “low female voice.” This alternate version favored Lenya (although some argue she was outside her vocal range at the Paris premiere).

In 1935, Weill and Lenya settled in the United States; they remarried the next year and, in 1943, Weill became a U.S. citizen.

In 1947, when a Life magazine article referred to Weill as a “German composer,” he wrote to them: “I have a gentle beef about one of your phrases. Although I was born in Germany, I do not consider myself a ‘German composer.’ The Nazis obviously did not consider me as such either, and I left their country (an arrangement which suited both me and my rulers admirably) in 1933. I am an American citizen, and during my dozen years in this country I have composed exclusively for the American stage.”

Photo credits:

Kurt Weill

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-2005-0119 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Bertolt Brecht

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-W0409-300 / Kolbe, Jörg / CC-BY-SA 3.0