Tomer Zvulun, Artistic & General Director of The Atlanta Opera chooses his FIVE THINGS you need to know about Die Walküre by Richard Wagner.

NUMBER 1: How does Die Walküre fit into the full Ring cycle of four music dramas?

Der Ring des Niebelungen (the Ring) is a tetralogy that includes four operas: Das Rheingold (“The Rhine Gold”), Die Walküre (“The Valkyrie”), Siegfried, and Gotterdammerung (“Twilight of the Gods”). Interestingly, Wagner called Das Rheingold “voreabend” — a preview or prelude. He named Die Walküre” erstabend” — the first evening. Though Das Rheingold is a full-scale opera, Wagner thought of it as Vorspiel, the introduction to the main attraction of Die Walküre and the operas that follow it. The question is “Why?”

Das Rheingold is a long-winded exposition that chronicles the origins of how the story begins: the gold is stolen from the river Rhine, the powerful ring is forged, and how the ring ends up in the hands of the giants. By the time we get to Die Walküre, we are introduced to the central conflict of the story and the central characters. This opera introduces us to new characters who are pivotal to the rest of the drama; Brunnhilde, Siegmund, and Sieglinde. Their actions drive the overarching storyline forward. Die Walküre concludes the exposition started in Das Rheingold and the action really begins.

NUMBER 2: Nature takes a profound symbolic role

The basic elements of nature: Water, Earth, Wind, and Fire, are important throughout the Ring. Both Das Rheingold and Die Walküre are bookended by scenes that feature primary elements of nature. Die Walküre opens with a spectacular storm sequence in a forest. A frightened man is running for his life chased by his mortal enemy. Through the music, you can feel the lightning flashes and the leaves rustling under his feet. The opera ends with a ring of fire surrounding Brunnhilde, the sleeping daughter of Wotan, the king of the gods. In contrast, Das Rheingold opens with water — a mesmerizing depiction of the depths of the river Rhine where the Rhein maidens guard the magical, precious gold. This serene, mystical setting embodies the purity of nature and the calming effect of water. At the end of Das Rheingold, Donner (the god of Thunder) summons a huge storm that results in a rainbow bridge on which the gods cross from the earth to their new heavenly abode: Valhalla. And so, Das Rheingold starts with water and ends with a storm, and Die Walküre starts with a storm and ends with fire.

NUMBER 3: The Human Condition

The Ring is built on two foundations. First is the glorious, popular, and seductive storytelling that is filled with special effects and characters. There are dragons, dungeons, gods, monsters, heroes, and a battle for the one ring to rule them all. Second, the other foundation, the one I am truly drawn to, is the depth of truth relating to the human condition.

The work of Richard Wagner, who wrote the massive libretto of the Ring, is saturated with philosophy. The work of significant thought leaders of the era, Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche are often mentioned in the same breath as the work of Wagner. The most powerful ideas in this aesthetic are the will to live and the will to power, expounding on the idea that the universal desire of every creature is to elevate their status, be it social, economic, or political. Everybody wants to control the magical ring of power. But Wagner tells us that there’s one rival to the love of power. Die Walküre tries to overcome the love of power with the power of love.

NUMBER 4: Love

“Love” is a problematic word in English because that one word tries to encapsulate so many meanings. Wagner, who was a great student of the Greeks, truly understood that “love” had many facets as the Greeks were aware. While the Greeks list eight types of love, I like to group them into five, with a couple of subsets.

Die Walküre is all about love and all its types.

Act 1 is all about Eros, as we meet Siegmund and Sieglinde who fall in love with a primal and fierce attraction. That erotic love is juxtaposed with the loveless, even abusive marriage between Sieglinde and Hunding.

Act 2 is a series of duets that explore a range of love types. Husband and wife (both Storge and Pragma); father and daughter (Storge); sister and brother (Storge); lovers who run away from society (Eros).

Act 3 is about a father who loves his daughter more than anything, but has the dawning realization that their closeness is coming to an end as she is becoming a woman with her own wishes and standards. His challenge is to let her go (Storge).

NUMBER 5: Is it possible to summarize the Ring?

The Ring is a complex story, arguably the largest and most complex saga in the history of music. It comprises four evenings, 15 hours of music featuring 58 leitmotifs, and dozens of roles. There’s no simple summary but there is merit to the exercise. There are two primary characters in the whole Ring: Wotan, king of the gods, and his arch-rival Alberich, chief of the Nibelungs. They represent the light and the dark. They come from different backgrounds and different caste systems, but they are after the same thing: ultimate power through the ring. From Das Rheingold, where these two are just starting their grasp for power, striving to get somewhere and willing to give up almost anything in the quest, we progress to Die Walküre — where Wotan starts to realize the magnitude of the curse that links the ring to the renunciation of all love. The desire for power is still strong enough to tempt him to pay the price — his own immortality and the destruction of his family.

Within the scope of the Ring, Die Walküre holds a special place because, at its core, it is a chamber opera (albeit with nearly 100 musicians in the pit!) made up of a bunch of intimate, LONG duets between characters who have strong loving relationships. The reason generations of people from around the world connect to this opera is that it reveals truth about the human condition. At the heart of the human condition is LOVE and the relationships that define us as humans. We must inherently connect to other people. This is the reason that I’m so fascinated with this story and I look forward to sharing it with you in Atlanta.

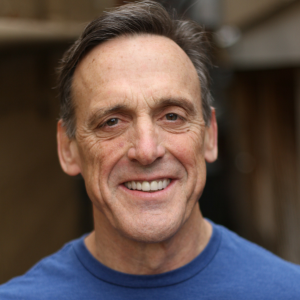

Tomer Zvulun, The Atlanta Opera’s Carl W. Knobloch Jr. General & Artistic Director, is featured on the cover of Atlanta Magazine’s Atlanta 500 issue!

He is one of Atlanta’s foremost leaders listed in the publication’s Film, Music & Entertainment section, alongside luminaries including Tyler Perry, Frank Patterson, Usher Raymond, and Kenny Blank.

The publication recognized his artistic achievements as an internationally renowned stage director, and the article also noted how The Atlanta Opera has grown during his tenure, with significantly increased fundraising, and double the number of productions per season.

This momentous occasion shines new light on our organization’s importance in Atlanta’s vibrant arts community. Thanks to the leadership of our board, generous support of our patrons, and tireless work of our staff, we face the future with hope, resolve and passion.

This blog post provides resources for educators, parents, students and the community to learn about opera.

In accordance with Governor Kemp’s recent order to close schools through the end of the 2019-20 school year, The Atlanta Opera Studio Tour performances of Hansel and Gretel have been cancelled. Here are some additional ideas to bring Hansel and Gretel into your virtual classroom.

After careful consideration, and with the health and safety of our patrons, staff and performers top of mind, we have decided to postpone he spring production of Madama Butterfly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Final Dress Rehearsal scheduled for April 30, 2020 at 7:00 p.m. has been cancelled. Here are some additional ideas to bring Madama Butterfly into your virtual classroom.

Please contact [email protected] with questions or concerns – we’re here to help!

“The rhythm section had him by the tail,

but there was no holding or cornering Bird.

Disappearing acts were his specialty.

Just when you thought you had him,

he’d move, coming up with another idea,

one that was as bold as red paint on a white sheet.”

Stanley Crouch

Charlie Parker biographer

By Noel Morris

HE WAS AN ADDICT, but his fluency of invention surpassed nearly every other figure in music. The tug between his genius and his tragic flaw set into motion the almost Shakespearean life of jazz legend Charlie Parker. But this opera isn’t just a history play, it’s ultimately about modern America: our music, our opioid crisis, and our racial inequity.

The idea of basing an opera on Charlie Parker touched a nerve for librettist Bridgette Wimberly: She had had an uncle who idolized him. As a young man, her mother’s brother became a sax player and a heroin addict. He played with Parker in a Cleveland nightclub and, like his muse, died young.

At the outset of this project, Wimberly immersed herself in Parker’s recordings, interviews, biographies, and contemporary accounts until she found the story she wanted to tell: a flight of fancy into what happened during the three days Parker laid dead and misidentified in a New York City morgue.

Those who’ve known an addict will recognize the diseased web that Parker spun: lies, theft, deception, broken promises, money troubles, and abandonment. Even the premise of Wimberly’s tale captures the mindset of an addict: As long as his misdeeds remain secret, they never happened. Composer Daniel Schnyder’s opera is a ghost story. The title character believes he can go on with his life as long as no one realizes he’s dead.

Hiding behind the confusion over his corpse, Charlie sets out to write his masterpiece — a reference to his interest in writing music more in the style of Stravinsky or Bartók.

Never one to look back, Charlie’s ghost plunges into his art. Death, however, has other ideas. One by one, the most important people and events in his Parker’s life return to envelope him like a blanket. In the end, he gives up on composition and sings the finale, “I know what the caged bird feels.” Here, Schnyder sets a text from the poem Sympathy by Paul Laurence Dunbar.

Charles Parker Jr., aka Yardbird or Bird, was born Aug. 29, 1920, in Kansas. His mom, a single mother, put an alto saxophone in his hand when he was 11. A few years later he left school to focus on music, teaching himself to play in all 12 keys (unconventional for jazz musicians). This became his foundation for blowing the top off any and all melodic possibilities.

By 16, Parker was already abusing heroin and alcohol. Then jazz drummer Jo Jones came to town. Sitting in on an open jam, Parker launched into one of his signature chromatic odysseys. That day, however, he couldn’t find his way back into the tune. Jones became angry and hurled a cymbal at Parker. Humiliated, Charlie went home and doubled down until he mastered the music that swirled inside his head. Note that Schnyder gives the character of Charlie a similarly virtuosic style, pushing the tenor to the outer extremes of his range and incorporating transcriptions of actual Charlie Parker solos).

At 19, Parker moved to New York City. Throughout his 20s he, along with Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk, pioneered a new kind of jazz known as bebop.

Parker married four times (three of his wives show up in the Yardbird ensemble). He fathered a son while still a teen in Kansas City but had little to do with the boy.

He had two more children with Chan, his common-law wife. In 1954, their 3-year-old daughter, Pree, died of cystic fibrosis. This tragedy sent Parker into a tailspin, and he landed in a California mental hospital, where he spent six months.

Parker lived his last days in New York’s Stanhope Hotel, in the suite of Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, a Rothschild known as Nica. She tried to get him to check himself into a hospital, but he refused. The official record indicates he died of pneumonia and a bleeding ulcer, although he also had a heart attack and advanced cirrhosis of the liver.

Nica, whose building was segregated, feared eviction. Her efforts to conceal Parker’s death delayed by five hours the delivery of his body to the morgue and caused confusion over his identity. Tabloids ran the headline “Bop King Dies in Heiress’ Flat.” Nica lost her apartment, her husband, custody of her children, and was disowned by her family.

The coroner registered Parker under the wrong name and estimated his age at 60. He was 34.

Charlie Parker’s Yardbird takes place in the nightclub that bears — capitalized on — his name: Birdland, a New York club that opened in December 1949. Parker headlined there for a short time but fell out with the owners because, co-owner Oscar Goodstein said, “He was continually wanting money.”

The Atlanta Opera: How long have you sung with The Atlanta Opera Chorus?

Lynnette Anderson: I’ve sung in The Atlanta Opera Chorus as a mezzo-soprano/alto since 1985, been in more than 80 productions, and have been featured in small ensembles in some productions.

AO: Where did you grow up and how did you get into music?

Lynnette: I grew up near Wheeling, W. Va., about an hour from Pittsburgh.

I can’t remember a time when I was not singing. I sang solos in church at a young age, I took piano lessons starting in the fifth grade, and I sang in school choirs. I received my music degrees from West Virginia University. Everything has always revolved around music.

AO: What are your favorite musical moments in Sweeney Todd?

Lynnette: “The Ballad of Sweeney Todd,” “Pirelli’s Miracle Elixir” scene, “Not While I’m Around,” and, of course, Mrs. Lovett’s “A Little Priest.”

AO: What is your all-time favorite Atlanta Opera moment?

Lynnette: I have several. The first time I stepped on the stage with the fabulous Atlanta Opera Chorus and Orchestra is a treasured moment. My first time singing the Moon Chorus, “Perchè tarda la Luna,” from Turandot. Being in the production of Orfeo with David Daniels, and the 1996 Olympics program at Symphony Hall, to name a few.

AO: What should audiences listen for in this opera?

Lynnette: The various themes that represent each character that are intertwined throughout Sweeney Todd.

AO: What do you do when you’re not singing?

Lynnette: When I first started singing in the chorus, I taught high school choral music, elementary music K-5, and sang as a staff singer in church choirs. I now help my husband with his production company and still sing in vocal groups around town. I love early music, so one of my goals is to become a virtuoso recorder player!

AO: Any advice for young singers?

Lynnette: The best advice I can give is from a quote by Gregory Hines: “Remember, luck is opportunity meeting up with preparation, so you must prepare yourself to be lucky.”

AO: Besides classical, what other genres of music and/or artists do you like?

Lynnette: I like all kinds of music–a little jazz, bluegrass, and Broadway tunes. When I’m in my car, I turn on Siriusly Sinatra on SiriusXM radio and croon along with him while driving. I do have a bumper sticker on my car that says, “Caution Driver Singing.”

AO: If you had to be another voice part, what would it be, and why?

Lynnette: Well, let’s see:

Who has some of the best music?

Who usually dies near the end of the opera?

Who is the primary love interest?

Which vocal part is always in demand in opera or chorus?

Answer: a tenor!

AO: Overrated or underrated: meat pies?

Lynnette: Underrated. Like liver and onions, you can’t get enough of Mrs. Lovett’s meat pies.

“The words of a survivor are like stars in the sky. They illuminate only a tiny piece of the past… No matter what is spoken of the night, there will always be more darkness than light.”

These lyrics from Out of Darkness: Two Remain speak to the vast resonance of the Third Reich’s atrocities that wiped out millions of people. Significant political and ethnic groups were persecuted because of their race, religion or sexual orientation. They were subjected to horrific hostility simply because of who they were. Jake Heggie’s new opera tells the powerful story of two survivors from that dark chapter in our history: a Jewish poet whose words inspired her fellow prisoners, and a gay man whose partner was executed because of his sexual orientation.

Growing up in Israel in the 1980s, I was surrounded by stories of holocaust survivors. As children, we naively saw them as the outcasts with funny accents and numbers tattooed on their arms. As I grew older, I remember being obsessed with their stories and amazed at the idea that another group of human beings was capable of such hate. For whatever reason, the stories of many extinguished souls remained in darkness.

Despite the ubiquity of these survival stories, we never heard tales of the persecution of gays during the holocaust. Marked by pink stars, more than one hundred thousand men and women were killed by the Nazis. Paragraph 175 in the German criminal law targeted any individual suspected of homosexuality. They could be arrested for a look or a touch, and thrown into a concentration camp. It baffles me that I knew so little about these stories until recently. Now, more than ever, it is time that we remember these people and bring their memories out of the darkness. This production is dedicated to the hundred thousand stars and many more that perished during the Third Reich.

The operas in our Discoveries series are selected to ignite difficult conversations, put a mirror up to our own selves, and to find resolution or even hope. Hope, in fact, is the message of Out of Darkness: Two Remain. The final lyric beautifully illuminates this message:

“The song of freedom upon our lips will never die.”

Tomer Zvulun

General & Artistic Director

Veteran Atlanta actor Tom Key was last seen at The Atlanta Opera as Pasha Selim in The Abduction from the Seraglio. As the Artistic Director of Theatrical Outfit, he helped to pave the way for a multidisciplinary collaboration on Out of Darkness: Two Remain, which fuses opera with theatre and dance, and will be performed at the 200-seat Balzer Theater at Herren’s/Theatrical Outfit in Downtown Atlanta. In Out of Darkness: Two Remain, Tom is Gad Beck, a gay German Jew who is confronted with the memory of his lost love. We chatted with him about this exciting collaboration, singing for the first time in an opera, and the significance of this world premiere.

What is the significance of having Out of Darkness: Two Remain performed at Theatrical Outfit?

It’s Sam Jackson cool. There was a moment during the end of our capital campaign when the whole effort could have collapsed short of a million dollars. There was pressure to compromise our plan and just build with what we had. If we had done that, we would have had a mediocre space with poor sight lines and bad acoustics. We held out, raised the last million within four weeks of our deadline and how have the beautiful home for Theatrical Outfit, The Balzer Theater at Herren’s. I could never have imagined that Tomer would come in our home a few years later and name it the best theater space in town.

Then there is the wonderful fact that our building used to be Herren’s restaurant, where in 1963 the owner, Ed Negri, under great threat of violence, became the first to integrate by inviting Dr. Lee and Delores Shelton to lunch. The Atlanta Opera and Theatrical Outfit’s collaboration on Out of Darkness: Two Remain is the reason I believe that 84 Luckie Street continues to be a place of healing and community.

I love the synchronization that this piece should follow our production of Perfect Arrangement. In different genres, from comedy to drama, both companies are focusing a light on topics of the most profound significance about the LGBT community.

How important is it to talk about the themes of Out of Darkness: Two Remain in our current world?

It is essential. It is not for nothing that the same ancient culture who gave us the idea by which we govern ourselves is also who gave us the theatre as we know it. At a time when democracy is in retreat and the institutions and norms that have upheld it are fragmenting we need this story. Out of Darkness: Two Remain makes it real for the audience that to “forget” or to “remember” are two of the most powerful choices we make that effect our future and the future of our children. The finale of the opera is not the end to an entertainment; it is the compelling and urgent invitation for us to work together toward our promised, bright, and common destiny.

You first performed with The Atlanta Opera as Pasha Selim in The Abduction from the Seraglio, but this will be your first singing role in an opera. How did you prepare?

When I read the libretto for Out of Darkness: Two Remain it was very much like reading poetry. Its meaning is not immediately apparent in a linear sense, but it is evident how it unlocks an incredibly powerful story that explodes in action between the characters. So, I learned the lines, meditated on them, let them incubate and then began to read and watch. I read Gad Beck’s “An Underground Life” and watched the documentary Paragraph 175; these were crucial to understanding this character and his journey.

I also began preparing the earliest I ever have – seven months out. Rolando Salazar happily agreed to meet with me last summer to work on “Farewell Auschwitz.” Honestly, I was prepared for him to say, “Tom, I think we have a problem and we need to talk to Tomer because you’re just too late to the game on this one to meet our standards.” Instead, after i had sung it through with him, he looked me in the eye and said, “Bravo.” I had sung with university choruses and in musicals before, but at that moment I felt like I’d landed on another shore of the brave new world of opera.

Out of Darkness: Two Remain is a true collaboration of opera, theatre, and dance. What has the creative process been like?

Mediocrity, lack of authenticity or a failure of courtesy are unacceptable within Tomer’s company. We show up intending for greatness, wanting to crack open the truth of the story and to do so with respect and kindness for one another. he continually asks questions, remains curious, dares us to stretch further, gently guides us to the best choices and celebrates our achievement when dramatic combustion is created. It’s a joyful process.

John and his dancers come into a room and transform it with their still, fearless presence. John will make a suggestion and create a movement–in the words of the libretto he offers a “look or a touch”–and the person to whom he is directing his nuclear creative energy is activated in all chakras. He begins with his dancers and it ripples through the rest of us in our words and voices and actions of our bodies in character. Their movement and energy perfectly supports, strengthens, and intensifies the story.

What are the challenges of the role?

The challenge is to not be overwhelmed by the enormity of the story and rather to stay focused step by step in the moment through to the end.

What is the most significant moment for Gad in this piece?

When Gad is in the presence of his true love, he finally remembers what he suffered and what he suffers for being who he is.

What should audiences expect at Out of Darkness: Two Remain?

To be transformed. To feel more human, more grateful for the miracle of life and more grateful for the miracle of one another, and even more willing to turn our trembling hearts closer to the light of courage and hope.

A note from composer Jake Heggie:

The persecution of gays during the Holocaust is not a topic that is much recognized or discussed. So Mina Miller [of Seattle-based Music of Remembrance] decided to take it on in a powerful and meaningful way: through music. When she called and asked me to create a new chamber composition based on this subject, I was deeply moved, excited, and hugely challenged. How on Earth could we find a way to do honor and justice to this subject? To recognize the suffering of so many in a 35-minute piece of music? The easy part was saying “Yes.” The hard part came next: the fascinating and moving journey of discovery.

As an opera composer — a theater man — I told Mina I’d want to include a singer and find a narrative. of some kind. She was very excited about this. I looked for poetry or stories from the time of WWII about this subject but found nothing. Baffled, I looked to more recent sources and was deeply upset to discover the reason why there was no material from the actual time: Homosexuality was against the law in Germany until 1970. Even after the camps were closed and the war was over, gays were considered criminals. So, after the war, they went into hiding or got married, fled, or just tried to blend in. Silence. The literary and art world began breaking this silence in the late 1970s (Martin Sherman’s 1979 play Bent, for example). But even in 2005, when the European Parliament — the elected parliamentary body of the European Union — drafted a resolution regarding the Holocaust, any mention of gay persecution was removed.

In my research, I went to the U.S. Holocaust Museum, read books about the subject, and eventually came across the extraordinary documentary film Paragraph 175. by Robert Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman. The film includes testimony from several gay men who were survivors of the camps. Here They are in their 70s, 80s and 90s, telling stories they never thought they’d be able to tell. Remarkable human stories: surprising, tragic, funny, hateful, shocking. I knew I wanted to use these stories but didn’t quite know how. it would happen. During this time, Mina Miller also sent me a link to the Holocaust Museum website that featured the journal of Manfred Lewin, a gay Jew who was murdered at Auschwitz with his entire family.

That’s when I realized I needed a librettist. to help put this all together. The elements were there, just not the story.

I had just worked with Gene Scheer on a new song cycle, and we were planning to write an opera together, so I asked him if he’d be interested. He was eager to do so. Gene is a tremendously gifted man, a songwriter as well as a librettist and lyricist. I shared with him the film Paragraph 175 and the books I’d found. He found books I didn’t know about, and Manfred Lewin’s journal, too. He was so excited when he read some of Manfred’s beautiful poetry, he called me right away.

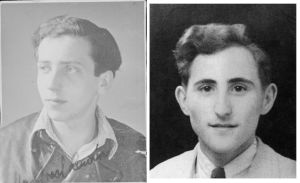

The journal was written for Gad Beck, who penned an autobiography and is a storyteller in Paragraph 175. Manfred and Gad were lovers as teenagers in Berlin until Manfred and his family were taken. In their love affair, we found the seeds of our story. We came up with the idea of an actor to play Gad in the present day, while the baritone would sing the role of Manfred. He would appear to Gad as a ghost one night. And through the two of them, we’d be able to share the stories from Paragraph 175 and the poetry of Manfred’s journal.

I chose the instruments in the ensemble because I wanted a variety of color so that I could include elements of jazz and swing, lyrical as well as the gritty instrumentation, and the percussive possibilities of the piano. including using the inside of the piano.

It is Manfred’s phrase “Do you remember?” that established the tone of the piece for me. In our story, Gad wants only to forget the horrors he lived through; Manfred, as a ghost, wants only to be remembered and wants Gad to remember their powerful, timeless love. There is a play between past and present. Musically, that was filled with rich possibilities. I found a tune for “Do you remember?” that served as the anchor of the piece. Most of the other material in the piece is connected to that tune.

A note from the composer, Jake Heggie:

The woman we know today as the author and lyricist Krystyna Żywulska was a Holocaust survivor with an astonishing, complex, sometimes baffling history. She was born Sonia Landau in 1914 to a Jewish family in Lódz, Poland, and was studying law at Warsaw University when World War II erupted.

In 1941, she and her family were relocated to the Warsaw ghetto. Seeing a window of an opportunity one day, Sonia and her mother walked out of the ghetto in broad daylight, leaving her father behind. She adopted the name Sophia Wisniewska and worked for the underground resistance until the Gestapo arrested her in 1943. Refusing to name names for the Nazis, she changed her own name to Krystyna Zywulska (born in 1918 rather than 1914) and was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau as a political prisoner (not a Jew).

She had no experience as a writer but crafted lyrics of protest and survival and set them to well-known folk tunes and popular melodies. It was suicide to write her lyrics down, so they were passed from inmate to inmate by word of mouth.

An inmate with some authority was moved by Krystyna’s work and decided to save the “camp poet.” After a year of disease, lice, and backbreaking labor in the fields, Krystyna was given one of the few choice jobs inside the Effektenkammer (warehouse of personal effects).

She and her co-workers took inventory and took charge of the possessions that thousands upon thousands of Jewish women and children from all over Europe brought with them to the camp. Often, once their possessions were taken and cataloged, the prisoners were marched next door to the ovens for execution. Krystyna heard the screams and cries, saw the smoke, smelled the stench, and had to live in an almost unimaginable situation: to survive, she had to take and catalogue the personal belongings of Jewish women and children, then hear them murdered next door.

At the end of the war, during a death march when the camp was being evacuated, Krystyna once again escaped and survived. After the war, She chronicled the atrocities she witnessed in a startlingly candid memoir, I Came Back (also titled I Survived Auschwitz), published in 1946. She still did not claim her Jewish identity. or ancestry. In the book, one feels strongly that Krystyna wanted to explain what happened without holding back.

The book is honest, revealing, and profoundly moving. It compels the reader to ponder the nature of memory and the parts of the past that remain in the shadows.

Act 1 of Out of Darkness: Two Remain explores those shadows, those empty places.

Krystyna Zywulska died in 1993, having reclaimed her Jewishness in the 1960s. She was interviewed late in life by Barbara Engleking for her nonfiction book Holocaust and Memory (published in Polish in 1994 and English in 2001). Krystyna’s responses to Engleking’s questions show her frustration in trying to find language that might adequately describe the enormity of what happened, or the extraordinary complexity in a fog of memories.

In that interview, a woman whose words saved her life now struggled to find words to describe what happened. It is This irony that prompted the idea for the scenario.

Of course, it is not that she couldn’t find the words. it is that none could ever truly describe what she and millions of others experienced. The past is thus clouded not by a lack of willingness to define what happened, but rather by the limits of language itself.

Like the uncertainty principal that governs the quantum heart of the world, history, too, seems to be ruled by immutable paradoxes. If you measure something, you change it. If you describe something, you change it as well — even the past.

Act 1 is about the struggle to describe harrowing, unimaginable situations to people who weren’t there. It is also about what it is to survive. Like many who make it through a war, Krystyna survived not through grand acts of heroism, but through near maddening acts of survival. We do whatever it takes to live another day: to see another sunrise.