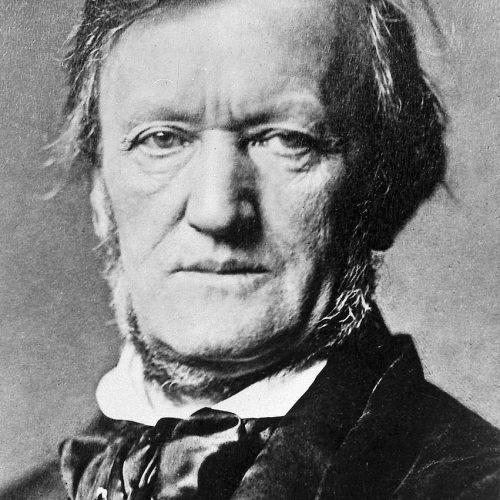

Richard Wagner molded opera according to his own creative definition with revolutionary zeal. Consequently, his innovations in melodic structure, harmony, characterization and orchestration have inspired awe among audiences and music professionals alike for over a century. Impressionist and expressionist composers have spent most of this century struggling to overcome his influence, rebelling against him. Wagner was a man who lived in capital letters and bold print, a study in superlatives: huge creative canvases, legendary feuds and hatreds, gigantic depressions and losses, enormous successes, and passionate romantic liaisons. His music represents the dynamic and incandescent final flowering of romanticism.

Egocentric from childhood, Wagner began at age twenty to record details of his personal and creative life in a series of journals, all in anticipation of drafting an extensive autobiography in later life. He never seems to have doubted his destiny or his own titanic genius. At first, Wagner fancied himself a writer and planned a career in the literary world, drafting a ghoulish drama, Leubald which killed off forty-two characters in the first four acts, with some returning as ghosts in the fifth.

Attendance at performances of Weber’s Der Freischutz and Beethoven’s Fidelio turned his attention toward a lifelong obsession with operatic composition. With his mother’s encouragement, he undertook the serious study of music, an academic process peppered with bouts of drinking, dueling, and gambling. Wagner’s father, at least in name, was Karl Friedrich Wagner, a police court clerk who died while his son was in infancy. In recent years, evidence gathered would indicate that Wagner’s biological father was actually Ludwig Geyer, a talented painter, dramatist and actor. Geyer married Wagner’s mother shortly after she was widowed.

He introduced his love of literature, art and theater into the household. Although Geyer died while Wagner was only eight years old, the stepfather’s influence had an indelible effect on the boy.

Wagner’s earliest works, two orchestral overtures, were completed in 1829 and received scornfully. A spare six months of formal music education came from Theodor Weinlig, cantor of the Thomasschule, in 1831. Those studies culminated in the composition of a Wagner symphony which was well-received in Leipzig and Prague. He began work on an opera Die Hochzeit , and tossed it aside unfinished, then completed a full operatic work Die Feen , which was destined not to be performed until five years after the composer’s death.

He undertook a series of conducting posts with small, sordid operatic companies, and there built the instinct and skills which would forge his colossal vision of musical drama. In 1836, Wagner married Minna Planer, an impulsive act he almost instantly regretted. Although mediocre, the union lasted until 1862.

Wagner struggled to establish himself in opera in Paris, living on the verge of starvation, from time to time imprisoned for his debts. Minna took in boarders. His preliminary sketches of the operas Rienzi and Das Liebesverbot were rejected by producers despite introductory letters from Giacomo Meyerbeer. Wagner staggered briefly under the humiliation, then turned to a new concept, The Flying Dutchman, and although impoverished and unknown declared himself victorious at its completion in 1841. He was not far from wrong. La Rienzi opened in Dresden in 1842 to enormous acclaim. A triumph followed the next year for The Flying Dutchman, in the same city.

Wagner became Kapellmeister of the Dresden opera and should have realized financial security at last. However, he continued to live far in excess of his means, accumulating impossible debts. Within the five years which followed, he had completed Tannhauser and Lohengrin. However, Lohengrin, which he considered his greatest effort to date was rejected by Dresden opera and, in anger, Wagner turned to revolution. He wrote handbills sympathetic to Dresden rioters who were creating a growing insurrection in the state of Saxony. When the revolution failed, Wagner was forced to flee to Paris.

During the thirteen years of Wagner’s exile, Lohengrin was presented in Weimar and was received tentatively just as Tannhauser had been. However, in the decade which followed both operas were embraced by German audiences. In fact, by the time his exile ended in 1860, Wagner was one of the few Germans who had never witnessed a performance of Lohengrin.

Years of high living had nearly bankrupted Wagner when, in 1864, the newly-crowned eighteen year old King Ludwig II became the composer’s devoted benefactor. Wagner produced Tristan and Isolde, Meistersinger, Das Rhinegold, and Die Walküre, in the five years between 1865 and 1870. However, his enormous persuasive influence on King Ludwig placed Wagner at the mercy of warring political factions who demanded the composer’s allegiance. Wagner refused all of them categorically. His refusal to engage in intrigue, combined with his involvement in a scandalous affair with the married daughter of Franz Lizst, Cosima von Bulow, drove Wagner from Munich. Wagner had indulged in numerous romantic liaisons in the past. However, in this case he had fathered a child whom his betrayed friend, Cosima’s husband Hans von Bulow, graciously accepted as his own. Cosima and Wagner acknowledged von Bulow’s discretion by naming the girl Isolde.

Once more in exile, Wagner continued receiving financial support from King Ludwig at a retreat near Lucerne, Switzerland. And, when his legal wife, Minna, died in 1866, he at last married Cosima.

The final years of Wagner’s life were dedicated to completion of the gargantuan music project – The Ring – which was to combine all the noblest forms of Art in its presentation: innovative melodic structure, ambitious orchestration and instrumentation, intensely dramatic characterization and evocative sets. His concept was immense: an orchestral, vocal and theatrical portrayal of the legendary struggle between gods and men for control of the earth. This compelling mythological drama would be presented over consecutive days in a series of four sequential operas: Das Rhinegold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung.

And to that end, he also undertook the construction of his concept of the perfect operatic performance facility at Bayreuth. When the theater opened for the first full performance of The Ring cycle on August 13, 1876, the event was attended by the luminaries of the musical world including Tchaikovsky, Saint-Saëns, Gounod, Grieg, and Liszt. Tchaikovsky noted, “Whether Wagner is right in pursuing his idea to the limit, or whether he stepped over the boundary of aesthetic conventions which can guarantee the durability of a work of art, whether musical art will progress further on the road started by Wagner, or whether the “Ring” is to be the point from which a reaction will set in remains to be seen. But in any case what happened in Bayreth will be well remembered by our grandchildren and our great-grandchildren.” And so it has been.

Wagner died suddenly of heart disease in 1883, having been seriously debilitated by his efforts at premiering his final work, Parsifal. He was buried in the garden of his home Wahnfried, at Bayreuth to the music of “Siegfried’s Death.”