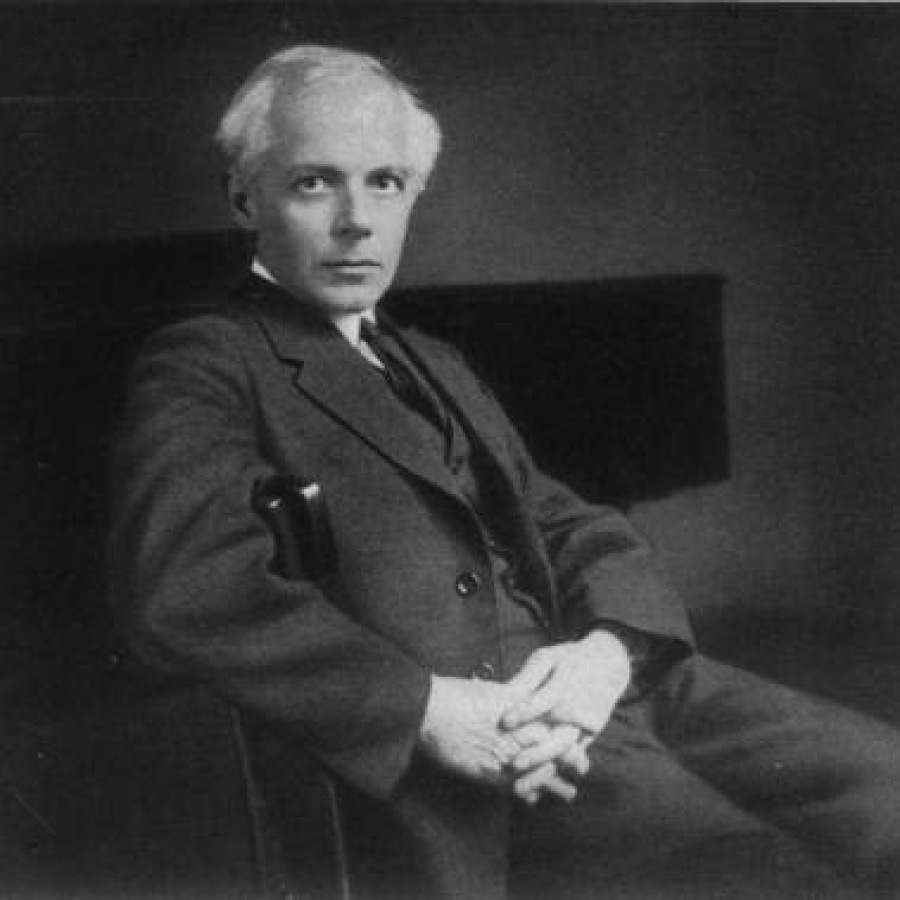

Bluebeard’s Castle is a one-act expressionist opera by Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. The original libretto was written by Béla Balázs, a poet and friend of the composer. The opera lasts only a little over an hour and there are only two singing characters onstage: Bluebeard, and his wife Judith.

In the original Hungarian version, the two have just eloped, and Judith is coming home to Bluebeard’s castle for the first time. Often described as a Gothic horror story, the story finds Judith uncovering Bluebeard’s sordid past and previous wives through the exploration of locked doors.

In the version performed in Atlanta, adapted from the Theatre of Sound in London, Judith and Bluebeard are grappling with the ramifications of Judith’s worsening dementia. The former “wives” she uncovers throughout the piece are in fact, memories of her past self.

In an interview with Opera Today, Daisy Evans, who adapted the libretto to English, explained, “It feels as if I’ve known the opera forever, and I’ve directed it in various forms – with the National Youth Orchestra and with Silent Opera [the company she founded to present explorations of staging and sound design in immersive productions of classic operas], and in 2019, again working with Stephen, in Castello di Potentino in the middle of Tuscany. And, every time there has seemed a mis-match between the Gothic elements of the story, such as the blood-stained keys, and Bartók’s music. The music is just too beautiful – it expresses the psychologies of the protagonists, it’s about love and loss and emotion. Bartók’s score is different to other representations of the tale. It’s more symbolic. So many productions present Bluebeard simply as a murderer of young women, but I can’t reconcile the music to this characterisation.”

In relation to her adaptation of the text, she added that the team “destroyed none of the original … it’s true to the original Hungarian, which is beautiful, abstract and ambiguous. The libretto doesn’t excavate Bluebeard’s character deeply. It’s a desperately sad experience for both of them, a terrible process. The ‘locked doors’ suggest a ‘terror mentality’. In reinventing, we’ve kept that familiar mystique but have taken the really precise specificity of the rooms in Bluebeard’s castle – the torture chamber, the armoury, the treasury – and applied them to moments in one’s life: the raising of a child, a marriage day, an argument. Often productions of the opera make Bluebeard seem rather passive but when the doors are opened, he is proud of his dominions. And, at the close three times, in a blank and monotonous tone, she says, “no more”: it is Judith who doesn’t want any more doors – in our reimagining, portals to memory – to be opened. And, we haven’t been literal: Judith doesn’t enter the chambers – each door is an atmosphere.”